“Long Covid” has long been the media’s justification for people to get vaccinated for Covid-19, regardless of prior infection to the virus. However, a recent longitudinal study by the National Institute of Health has thrown into question whether vaccines have strong efficacy against “long Covid.”

As explained in Nature Medicine, post-acute sequelae of Covid-19 or PASC, also called “long COVID,” is “an umbrella term used to describe chronic outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection.” It states that a “prominent subset of patients with PASC includes those who experience a syndrome characterized by unexplained exertion intolerance, debilitating fatigue, cognitive and sensory disturbances, headaches, myalgia, and recurrent flu-like symptoms.” Covid-19 is not unique in triggering such lingering debilitating symptoms, the authors point out.

On Wednesday, Nature Medicine published a new report that shows vaccination does not appear to provide nearly the amount of protection against “long Covid” as was previously claimed.

“The post-acute sequelae of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection—also referred to as Long COVID—have been described, but whether breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection (BTI) in vaccinated people results in post-acute sequelae is not clear,” the Nature Medicine study states.

“In this study, we used the US Department of Veterans Affairs national healthcare databases to build a cohort of 33,940 individuals with BTI and several controls of people without evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including contemporary (n = 4,983,491), historical (n = 5,785,273) and vaccinated (n = 2,566,369) controls. At 6 months after infection, we show that, beyond the first 30 days of illness, compared to contemporary controls, people with BTI exhibited a higher risk of death (hazard ratio (HR) = 1.75, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.59, 1.93) and incident post-acute sequelae (HR = 1.50, 95% CI: 1.46, 1.54), including cardiovascular, coagulation and hematologic, gastrointestinal, kidney, mental health, metabolic, musculoskeletal and neurologic disorders.”

“The results were consistent in comparisons versus the historical and vaccinated controls,” the study adds. “Compared to people with SARS-CoV-2 infection who were not previously vaccinated (n = 113,474), people with BTI exhibited lower risks of death (HR = 0.66, 95% CI: 0.58, 0.74) and incident post-acute sequelae (HR = 0.85, 95% CI: 0.82, 0.89). Altogether, the findings suggest that vaccination before infection confers only partial protection in the post-acute phase of the disease; hence, reliance on it as a sole mitigation strategy may not optimally reduce long-term health consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection. The findings emphasize the need for continued optimization of strategies for primary prevention of BTI and will guide development of post-acute care pathways for people with BTI.”

The statistical upshot of the 0.66 HR or “Hazard Ratio” is that vaccines appear to be 33% effective at preventing mortality after Covid-19 breakthrough infections versus the mortality rate for those who were unvaccinated and became infected with Covid-19.

Critically, the Covid vaccines were only 15% effective at preventing “Long Covid.” This analysis was corroborated by Dr. Eric Topol, a cardiologist who is a medical analyst for Scripps Research.

Just out @NatureMedicine

The natural history of post-vaccine breakthrough infections (BTI) in 33,000 people, >13 million controlshttps://t.co/2JUuTab5fl@zalaly @BCBowe @Biostayan @WUSTLmed

—Vaccination protection from #LongCovid ~15%, much less than many other studies (~50%) pic.twitter.com/Ur7vQTKmOC— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) May 25, 2022

s41591-022-01840-0BTI relative risk and absolute excess burden at 6 months for death, particularly increased for clot-related, lung sequelae pic.twitter.com/em3KgnPxoM

— Eric Topol (@EricTopol) May 25, 2022

“The natural history of post-vaccine breakthrough infections (BTI) in 33,000 people, >13 million controls,” Dr. Topol writes. “Vaccination protection from #LongCovid ~15%, much less than many other studies (~50%).”

Detailed analysis of the study was also provided by Harvard Medical School professor Adam W. Gaffney.

An important new study is out. Baseline findings from the NIH's longitudinal, intramural Long COVID study — perhaps the most detailed, controlled, comprehensive investigation of multiple health metrics in this setting thus far conducted — were just published in @AnnalsIM

A🧵

1/— Adam W Gaffney (@awgaffney) May 23, 2022

“First, as you’d expect, most (84%) of those post-COVID had anti-COVID-19 antibodies, and (by design) none of the controls,” Gaffney writes in the thread. “Second, vs controls, those post-COVID group reported significantly more symptoms, e.g. fatigue, shortness of breath, anosmia [loss of smell, ed.], headache, & more.”

“On the other hand, numerous biomarkers showed no difference between those post-COVID and controls, including tests for”:

(1) general inflammation (e.g. CRP)

(2) autoimmunity (e.g. ANA)

(3) clotting abnormality (e.g. d-dimer)

(4) heart inflammation (e.g. troponin)

(5) Kidney function

(6) Liver function

(7) Blood levels

(8) Brain injury (neurofilament light chains)

“Next, they report lung function tests,” Gaffney goes on. “Again, no differences, unsurprising given that the post-COVID patients mostly did not have severe pneumonia which damages the lungs.”

“In terms of heart function, assessed with ultrasound: Again, no differences between post-COVID subjects and controls,” he contiues. “There was no difference in percent with low oxygen levels either. There was a distance in walk distance over 6-minutes compared to controls: 560m vs. 595m.”

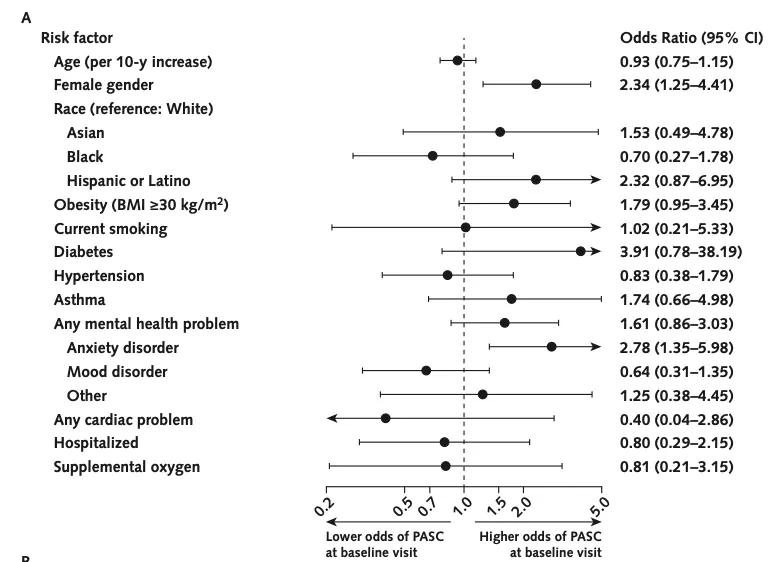

“The investigators identified few pre-COVID-19 risk factors for PASC, e.g. a history of an anxiety disorder. In contrast, there were no correlations between any of the diagnostic tests and the presence of PASC,” he added.

“There were no differences in neurocognitive testing between the groups, e.g. in processing speed, episodic memory, or executive functioning,” Gaffney said. “However, quality of life, both physical and in terms of mental health, was much lower post-COVID compared to controls. Notably, post-COVID patients were much more likely to have high anxiety scores and depression scores, particularly anxiety with PASC.”

Thus, the Harvard Medical School professor is laying out a case that Long Covid has a mostly psychological (although not unsubstantial) impact for most patients.

“How about evidence of persistent inflammation or infection post-COVID?” Gaffney continued. “They assessed numerous inflammatory biomarkers (e.g. macrophage inflammatory protein-1b , INF-G, TNF-alpha) and found no difference in levels of more than 10 of them. A single marker was higher in COVID-19 subjects vs. controls, but not in PASC vs. non-PASC.”

“There was little difference in the frequencies of different types of T cells that can be an indicator of immune activation,” he went on. “Overall, no real evidence of ongoing inflammation. Finally, no substantive evidence of persistence viral infection in nose or blood.”

“To summarize, there was a large burden of symptoms & worse mental health post-COVID (particularly among those with PASC) but no difference in objective neurocognition, & no evidence of ‘ongoing systemic inflammation or immune activation’ or any organ damage,” Gaffney adds.

This should be a relief to many affected with Long Covid that there may be psychological treatments that may alleviate the symptoms. The research also may provide critical insights into what constitutes “Long Covid” versus potential vaccine and booster shot side effects.

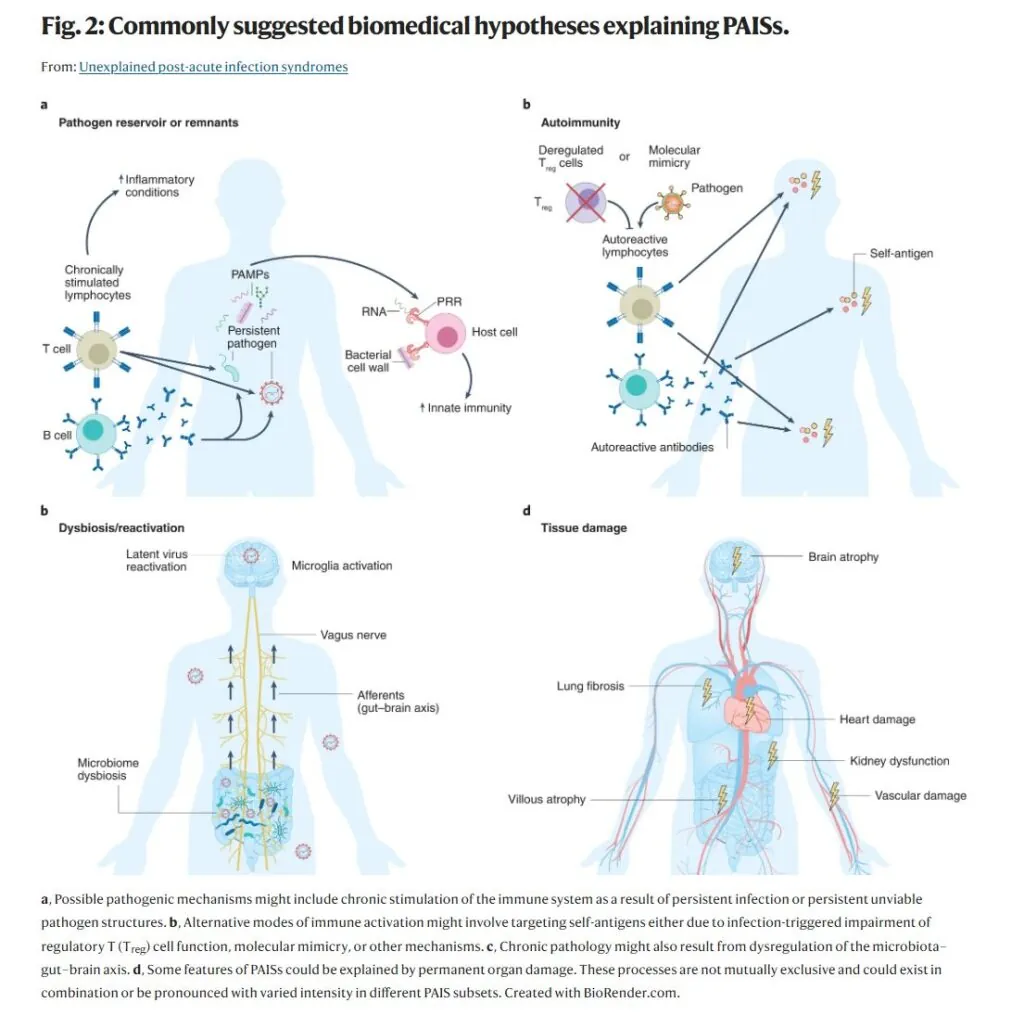

The journal Nature Medicine on May 18 published an article on “Unexplained post-acute infection syndromes.” It rightly states that “post-acute infection syndromes” (PAISs), such as “long Covid,” have been underresearched and have suffered from a lack of objective data.

“Although known for a long time, little attention has been paid to the chronic sequelae described in a proportion of exposed individuals following certain infections,” the authors write. “Despite the significant worldwide impact of such chronic illnesses, they often go undiagnosed owing to the nonspecific nature of symptoms and a lack of objective diagnostic findings. These ‘tails’ of acute infectious diseases, herein referred to as PAISs, are characterized by an unexplained failure to recover from the acute infection, although studies of objective markers have so far been mostly unrevealing, and the pathogen rarely remains detectable by commonly used methods.”

The article proceeds to discuss post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) or ‘long COVID.’ It suggests that Covid-19 is by no means unique in its post-infection pathology.

“It is remarkable that PASC, especially when it occurs after mild or moderate (rather than severe) COVID-19, shares many similarities with chronic illnesses triggered by other pathogenic organisms, many of which have not been sufficiently explained,” the article explains. “These PAISs are characterized by a set of core symptoms centering on exertion intolerance, disproportionate levels of fatigue, neurocognitive and sensory impairment, flu-like symptoms, unrefreshing sleep, myalgia/arthralgia, and a plethora of nonspecific symptoms that are often present but variably pronounced. These similarities suggest a unifying pathophysiology that needs to be elucidated to properly understand and manage post-infectious chronic disability.”

The Nature Medicine article provides a very useful chart that show the prevalence of long Covid self-reporting versus ‘healthy unexposed controls.’ (See: chart b).

It also provides a snapshot of various valid medical hypotheses about PostAcute Infection Syndromes (PAISs).

The NIH study is a step in the right direction towards remedying the lack of research on “long Covid.” But much more research needs to be undertaken to gain more clarity on the syndrome and to separate media fact from medical fiction.