Antibody-dependent enhancement and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapies

Nature Microbiology volume 5, pages1185–1191 (2020)

Abstract

Antibody-based drugs and vaccines against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) are being expedited through preclinical and clinical development. Data from the study of SARS-CoV and other respiratory viruses suggest that anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies could exacerbate COVID-19 through antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). Previous respiratory syncytial virus and dengue virus vaccine studies revealed human clinical safety risks related to ADE, resulting in failed vaccine trials. Here, we describe key ADE mechanisms and discuss mitigation strategies for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapies in development. We also outline recently published data to evaluate the risks and opportunities for antibody-based protection against SARS-CoV-2.

Main

The emergence and rapid global spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has resulted in substantial global morbidity and mortality along with widespread social and economic disruption. SARS-CoV-2 is a betacoronavirus closely related to SARS-CoV (with ~80% sequence identity), which caused the SARS outbreak in 2002. Its next closest human coronavirus relative is Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus (MERS-CoV; ~54% sequence identity), which caused Middle East respiratory syndrome in 2012 (refs. 1,2). SARS-CoV-2 is also genetically related to other endemic human coronaviruses that cause milder infections: HCoV-HKU1 (~52% sequence identity), HCoV-OC43 (~51%), HCoV-NL63 (~49%) and HCoV-229E (~48%)1. SARS-CoV-2 is even more closely related to coronaviruses identified in horseshoe bats, suggesting that horseshoe bats are the primary animal reservoir with a possible intermediate transmission event in pangolins3.

Cellular entry of SARS-CoV-2 is mediated by the binding of the viral spike (S) protein to its cellular receptor, angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2)4,5. Other host entry factors have been identified, including neuropilin-1 (refs. 6,7) and TMPRSS2, a transmembrane serine protease involved in S protein maturation4. The SARS-CoV-2 S protein consists of the S1 subunit, which contains the receptor binding domain (RBD), and the S2 subunit, which mediates membrane fusion for viral entry8. A major goal of vaccine and therapeutic development is to generate antibodies that prevent the entry of SARS-CoV-2 into cells by blocking either ACE2–RBD binding interactions or S-mediated membrane fusion.

One potential hurdle for antibody-based vaccines and therapeutics is the risk of exacerbating COVID-19 severity via antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). ADE can increase the severity of multiple viral infections, including other respiratory viruses such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)9,10 and measles11,12. ADE in respiratory infections is included in a broader category named enhanced respiratory disease (ERD), which also includes non-antibody-based mechanisms such as cytokine cascades and cell-mediated immunopathology (Box 1). ADE caused by enhanced viral replication has been observed for other viruses that infect macrophages, including dengue virus13,14 and feline infectious peritonitis virus (FIPV)15. Furthermore, ADE and ERD has been reported for SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV both in vitro and in vivo. The extent to which ADE contributes to COVID-19 immunopathology is being actively investigated.

In this Perspective, we discuss the possible mechanisms of ADE in SARS-CoV-2 and outline several risk mitigation principles for vaccines and therapeutics. We also highlight which types of studies are likely to reveal the relevance of ADE in COVID-19 disease pathology and examine how the emerging data might influence clinical interventions.

Mechanisms of ADE

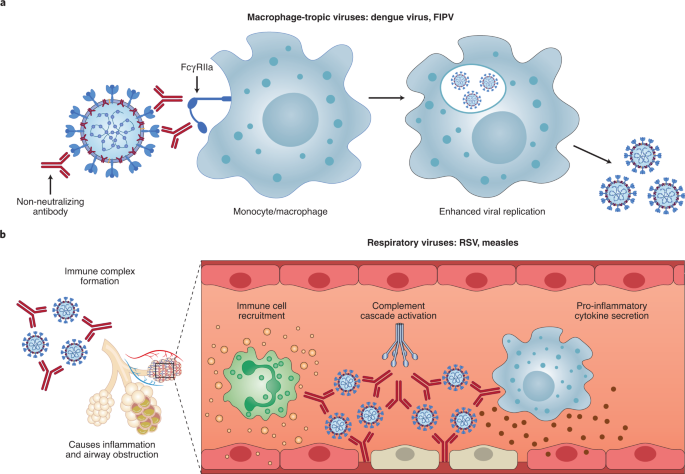

ADE has been documented to occur through two distinct mechanisms in viral infections: by enhanced antibody-mediated virus uptake into Fc gamma receptor IIa (FcγRIIa)-expressing phagocytic cells leading to increased viral infection and replication, or by excessive antibody Fc-mediated effector functions or immune complex formation causing enhanced inflammation and immunopathology (Fig. 1, Box 1). Both ADE pathways can occur when non-neutralizing antibodies or antibodies at sub-neutralizing levels bind to viral antigens without blocking or clearing infection. ADE can be measured in several ways, including in vitro assays (which are most common for the first mechanism involving FcγRIIa-mediated enhancement of infection in phagocytes), immunopathology or lung pathology. ADE via FcγRIIa-mediated endocytosis into phagocytic cells can be observed in vitro and has been extensively studied for macrophage-tropic viruses, including dengue virus in humans16 and FIPV in cats15. In this mechanism, non-neutralizing antibodies bind to the viral surface and traffic virions directly to macrophages, which then internalize the virions and become productively infected. Since many antibodies against different dengue serotypes are cross-reactive but non-neutralizing, secondary infections with heterologous strains can result in increased viral replication and more severe disease, leading to major safety risks as reported in a recent dengue vaccine trial13,14. In other vaccine studies, cats immunized against the FIPV S protein or passively infused with anti-FIPV antibodies had lower survival rates when challenged with FIPV compared to control groups17. Non-neutralizing antibodies, or antibodies at sub-neutralizing levels, enhanced entry into alveolar and peritoneal macrophages18, which were thought to disseminate infection and worsen disease outcome19.

a, For macrophage-tropic viruses such as dengue virus and FIPV, non-neutralizing or sub-neutralizing antibodies cause increased viral infection of monocytes or macrophages via FcγRIIa-mediated endocytosis, resulting in more severe disease. b, For non-macrophage-tropic respiratory viruses such as RSV and measles, non-neutralizing antibodies can form immune complexes with viral antigens inside airway tissues, resulting in the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, immune cell recruitment and activation of the complement cascade within lung tissue. The ensuing inflammation can lead to airway obstruction and can cause acute respiratory distress syndrome in severe cases. COVID-19 immunopathology studies are still ongoing and the latest available data suggest that human macrophage infection by SARS-CoV-2 is unproductive. Existing evidence suggests that immune complex formation, complement deposition and local immune activation present the most likely ADE mechanisms in COVID-19 immunopathology. Figure created using BioRender.com.

In the second described ADE mechanism that is best exemplified by respiratory pathogens, Fc-mediated antibody effector functions can enhance respiratory disease by initiating a powerful immune cascade that results in observable lung pathology20,21. Fc-mediated activation of local and circulating innate immune cells such as monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells and natural killer cells can lead to dysregulated immune activation despite their potential effectiveness at clearing virus-infected cells and debris. For non-macrophage tropic respiratory viruses such as RSV and measles, non-neutralizing antibodies have been shown to induce ADE and ERD by forming immune complexes that deposit into airway tissues and activate cytokine and complement pathways, resulting in inflammation, airway obstruction and, in severe cases, leading to acute respiratory distress syndrome10,11,22,23. These prior observations of ADE with RSV and measles have many similarities to known COVID-19 clinical presentations. For example, over-activation of the complement cascade has been shown to contribute to inflammatory lung injury in COVID-19 and SARS24,25. Two recent studies found that S- and RBD-specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies in patients with COVID-19 have lower levels of fucosylation within their Fc domains26,27—a phenotype linked to higher affinity for FcγRIIIa, an activating Fc receptor (FcR) that mediates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. While this higher affinity can be beneficial in some cases via more vigorous FcγRIIIa-mediated effector functions28,29, non-neutralizing IgG antibodies against dengue virus that were afucosylated were associated with more severe disease outcomes30. Larsen et al. further show that S-specific IgG in patients with both COVID-19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome had lower levels of fucosylation compared to patients who had asymptomatic or mild infections26. Whether the lower levels of fucosylation of SARS-CoV-2-specific antibodies directly contributed to COVID-19 immunopathology remains to be determined.

Importantly, SARS-CoV-2 has not been shown to productively infect macrophages31,32. Thus, available data suggest that the most probable ADE mechanism relevant to COVID-19 pathology is the formation of antibody–antigen immune complexes that leads to excessive activation of the immune cascade in lung tissue (Fig. 1).

Evidence of ADE in coronavirus infections in vitro

While ADE has been well documented in vitro for a number of viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)33,34, Ebola35,36, influenza37 and flaviviruses38, the relevance of in vitro ADE for human coronaviruses remains less clear. Several studies have shown increased uptake of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV virions into FcR-expressing monocytes or macrophages in vitro32,39,40,41,42. Yip et al. found enhanced uptake of SARS-CoV and S-expressing pseudoviruses into monocyte-derived macrophages mediated by FcγRIIa and anti-S serum antibodies32. Similarly, Wan et al. showed that a neutralizing monoclonal antibody (mAb) against the RBD of MERS-CoV increased the uptake of virions into macrophages and various cell lines transfected with FcγRIIa39. However, the fact that antigen-specific antibodies drive phagocytic uptake is unsurprising, as monocytes and macrophages can mediate antibody-dependent phagocytosis via FcγRIIa for viral clearance, including for influenza43. Importantly, macrophages in infected mice contributed to antibody-mediated clearance of SARS-CoV44. While MERS-CoV has been found to productively infect macrophages45, SARS-CoV infection of macrophages is abortive and does not alter the pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression profile after antibody-dependent uptake41,42. Findings to date argue against macrophages as productive hosts of SARS-CoV-2 infection31,32.

ADE in human coronavirus infections

No definitive role for ADE in human coronavirus diseases has been established. Concerns were first raised for ADE in patients with SARS when seroconversion and neutralizing antibody responses were found to correlate with clinical severity and mortality46. A similar finding in patients with COVID-19 was reported, with higher antibody titres against SARS-CoV-2 being associated with more severe disease47. One simple hypothesis is that greater antibody titres in severe COVID-19 cases result from higher and more prolonged antigen exposure due to higher viral loads48,49. However, a recent study showed that viral shedding in the upper respiratory tract was indistinguishable between patients with asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 (ref. 50). Symptomatic patients showed higher anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibody titres and cleared the virus from the upper respiratory tract more quickly, contradicting a simpler hypothesis that antibody titres are simply caused by higher viral loads. Other studies showed that anti-SARS-CoV-2 T-cell responses could be found at high levels in mild and asymptomatic infections51,52. Taken together, the data suggest that strong T-cell responses can be found in patients with a broad range of clinical presentations, whereas strong antibody titres are more closely linked to severe COVID-19. One important caveat is that viral shedding was measured in the upper respiratory tract rather than in the lower respiratory tract50. The lower respiratory tract is likely more important for severe COVID-19 lung pathology, and it is unclear how closely SARS-CoV-2 viral shedding in the upper and lower respiratory tracts correlate throughout the disease course.

Beyond the host response to new SARS-CoV-2 infections, the potential of pre-existing antibodies against other human coronavirus strains to mediate ADE in patients with COVID-19 is another possible concern53. Antibodies elicited by coronavirus strains endemic in human populations (such as HKU1, OC43, NL63 and 229E) could theoretically mediate ADE by facilitating cross-reactive recognition of SARS-CoV-2 in the absence of viral neutralization. Preliminary data show that antibodies from SARS-CoV-2-naïve donors who had high reactivity to seasonal human coronavirus strains were found to have low levels of cross-reactivity against the nucleocapsid and S2 subunit of SARS-CoV-2 (ref. 54). Whether such cross-reactive antibodies can contribute to clinical ADE of SARS-COV-2 remains to be addressed.

Risk of ERD for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

Safety concerns for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were initially fuelled by mouse studies that showed enhanced immunopathology, or ERD, in animals vaccinated with SARS-CoV following viral challenge55,56,57,58. The observed immunopathology was associated with Th2-cell-biased responses55 and was largely against the nucleocapsid protein56,58. Importantly, immunopathology was not observed in challenged mice following the passive transfer of nucleocapsid-specific immune serum56, confirming that the enhanced disease could not be replicated using the serum volumes transferred. Similar studies using inactivated whole-virus or viral-vector-based vaccines for SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV resulted in immunopathology following viral challenge59,60,61, which were linked to Th2-cytokine-biased responses55 and/or excessive lung eosinophilic infiltration57. Rational adjuvant selection ensures that Th1-cell-biased responses can markedly reduce these vaccine-associated ERD risks. Candidate SARS-CoV vaccines formulated with either alum, CpG or Advax (a delta inulin-based adjuvant) found that while the Th2-biased responses associated with alum drove lung eosinophilic immunopathology in mice, protection without immunopathology and a more balanced Th1/Th2 response were induced by Advax62. Hashem et al. showed that mice vaccinated with an adenovirus 5 viral vector expressing MERS-CoV S1 exhibited pulmonary pathology following viral challenge, despite conferring protection. Importantly, the inclusion of CD40L as a molecular adjuvant boosted Th1 responses and prevented the vaccine-related immunopathology63.

Should it occur, ERD caused by human vaccines will first be observed in larger phase II and/or phase III efficacy trials that have sufficient infection events for statistical comparisons between the immunized and placebo control study arms. Safety profiles of COVID-19 vaccines should be closely monitored in real time during human efficacy trials, especially for vaccine modalities that may have a higher theoretical potential to cause immunopathology (such as inactivated whole-virus formulations or viral vectors)64,65.

Risk of ADE for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines

Evidence for vaccine-induced ADE in animal models of SARS-CoV is conflicting, and raises potential safety concerns. Liu et al. found that while macaques immunized with a modified vaccinia Ankara viral vector expressing the SARS-CoV S protein had reduced viral replication after challenge, anti-S IgG also enhanced pulmonary infiltration of inflammatory macrophages and resulted in more severe lung injury compared to unvaccinated animals66. They further showed that the presence of anti-S IgG prior to viral clearance skewed the wound-healing response of macrophages into a pro-inflammatory response. In another study, Wang et al. immunized macaques with four B-cell peptide epitopes of the SARS-CoV S protein and demonstrated that while three peptides elicited antibodies that protected macaques from viral challenge, one of the peptide vaccines induced antibodies that enhanced infection in vitro and resulted in more severe lung pathology in vivo67.

In contrast, to determine whether low titres of neutralizing antibodies could enhance infection in vivo, Luo et al. challenged rhesus macaques with SARS-CoV nine weeks post-immunization with an inactivated vaccine, when neutralizing antibody titres had waned below protective levels68. While most immunized macaques became infected following viral challenge, they had lower viral titres compared to placebo controls and did not show higher levels of lung pathology. Similarly, Qin et al. showed that an inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine protected cynomolgus macaques from viral challenge and did not result in enhanced lung immunopathology, even in macaques with low neutralizing antibody titres69. A study in hamsters demonstrated that despite enhanced in vitro viral entry into B cells via FcγRII, animals vaccinated with the recombinant SARS-CoV S protein were protected and did not show enhanced lung pathology following viral challenge70.

SARS-CoV immunization studies in animal models have thus produced results that vary greatly in terms of protective efficacy, immunopathology and potential ADE, depending on the vaccine strategy employed. Despite this, vaccines that elicit neutralizing antibodies against the S protein reliably protect animals from SARS-CoV challenge without evidence of enhancement of infection or disease71,72,73. These data suggest that human immunization strategies for SARS-CoV-2 that elicit high neutralizing antibody titres have a high chance of success with minimal risk of ADE. For example, subunit vaccines that can elicit S-specific neutralizing antibodies should present lower ADE risks (especially against S stabilized in the prefusion conformation, to reduce the presentation of non-neutralizing epitopes8). These modern immunogen design approaches should reduce potential immunopathology associated with non-neutralizing antibodies.

Vaccines with a high theoretical risk of inducing pathologic ADE or ERD include inactivated viral vaccines, which may contain non-neutralizing antigen targets and/or the S protein in non-neutralizing conformations, providing a multitude of non-protective targets for antibodies that could drive additional inflammation via the well-described mechanisms observed for other respiratory pathogens. However, it is encouraging that a recent assessment of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine elicited strong neutralizing antibodies in mice, rats and rhesus macaques, and provided dose-dependent protection without evidence of enhanced pathology in rhesus macaques74. Going forward, increased vaccine studies in the Syrian hamster model may provide critical preclinical data, as the Syrian hamster appears to replicate human COVID-19 immunopathology more closely than rhesus macaque models75.

ADE and recombinant antibody interventions

The discovery of mAbs against the SARS-CoV-2 S protein is progressing rapidly. Recent advances in B-cell screening and antibody discovery have enabled the rapid isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies from convalescent human donors76,77 and immunized animal models78, and through re-engineering previously identified SARS-CoV antibodies79. Many more potently neutralizing antibodies will be identified in the coming weeks and months, and several human clinical trials are ongoing in July 2020. Human trials will comprise both prophylactic and therapeutic uses, both for single mAbs and cocktails. Some human clinical trials are also incorporating FcR knockout mutations to further reduce ADE risks80. Preclinical data suggest a low risk of ADE for potently neutralizing mAbs at doses substantially above the threshold for neutralization, which protected mice and Syrian hamsters against SARS-CoV-2 challenge without enhancement of infection or disease81,82. ADE risks could increase in the time period where mAb concentrations have waned below a threshold for protection (which is analogous to the historical mother–infant data that provided important clinical evidence for ADE in dengue83). The sub-protective concentration range will likely occur several weeks or months following mAb administration, when much of the initial drug dose has cleared the body. Notably, Syrian hamsters given low doses of an RBD-specific neutralizing mAb prior to challenge with SARS-CoV-2 showed a trend for greater weight loss than control animals82, though differences were not statistically significant and the low-dose animals had lower viral loads in the lung compared to control animals. Non-neutralizing mAbs against SARS-CoV-2 could also be administered before or after infection in a hamster model to determine whether non-neutralizing antibodies enhance disease. Passive transfer of mAbs at various time points after infection (for example, in the presence of high viral loads during peak infection) could also address the question of whether immune complex formation and deposition results in the enhancement of disease and lung immunopathology. If ADE of neutralizing or non-neutralizing mAbs is a concern, the Fc portion of these antibodies could be engineered with mutations that abrogate FcR binding80. Animal studies can help to inform whether Fc-mediated effector functions are crucial in preventing, treating or worsening SARS-CoV-2 infection, in a similar way to previous studies of influenza A and B infection in mice84,85 and simian-HIV infection in macaques86,87. An important caveat for testing human mAbs in animal models is that human antibody Fc regions may not interact with animal FcRs in the same way as human FcRs88. Whenever possible, antibodies used for preclinical ADE studies will require species-matched Fc regions to appropriately model Fc effector function.

ADE and convalescent plasma interventions

Convalescent plasma (CP) therapy has been used to treat patients with severe disease during many viral outbreaks in the absence of effective antiviral therapeutics. It can offer a rapid solution for therapies until molecularly defined drug products can be discovered, evaluated and produced at scale. While there is a theoretical risk that CP antibodies could enhance disease via ADE, case reports in SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV outbreaks showed that CP therapy was safe and was associated with improved clinical outcomes89,90. One of the largest studies during the SARS outbreak reported the treatment of 80 patients with SARS in Hong Kong91. While there was no placebo control group, no CP-associated adverse effects were detected and there was a higher discharge rate among patients treated earlier in infection. Several small studies of individuals with severe COVID-19 disease and a study of 5,000 patients with COVID-19 have shown that CP therapy appears safe and may improve disease outcomes92,93,94,95,96, although the benefits appear to be mild97. However, it is difficult to determine whether CP therapy contributed to recovery as most studies to date were uncontrolled and many patients were also treated with other drugs, including antivirals and corticosteroids. The potential benefits of CP therapy in patients with severe COVID-19 is also unclear, as patients with severe disease may have already developed high antibody titres against SARS-CoV-2 (refs. 47,98). CP has been suggested for prophylactic use in high-risk populations, including people with underlying risk factors, frontline healthcare workers and people with exposure to confirmed COVID-19 cases99. CP for prophylactic use may pose an even lower ADE risk compared to its therapeutic use, as there is a lower antigenic load associated with early viral transmission compared to established respiratory infection. As we highlighted above with recombinant mAbs, and as shown in historical dengue virus mother–infant data, the theoretical risk of ADE in CP prophylaxis is highest in the weeks following transfusion, when antibody serum neutralization titres fall to sub-protective levels. ADE risks in CP studies will be more difficult to quantify than in recombinant mAb studies because the precise CP composition varies widely across treated patients and treatment protocols, especially in CP studies that are performed as one-to-one patient–recipient protocols without plasma pooling.

To mitigate potential ADE risks in CP therapy and prophylaxis, plasma donors could be pre-screened for high neutralization titres. Anti-S or anti-RBD antibodies could also be purified from donated CP to enrich for neutralizing antibodies and to avoid the risks of ADE caused by non-neutralizing antibodies against other SARS-CoV-2 antigens. Passive infusion studies in animal models are helping to clarify CP risks in a well-controlled environment, both for prophylactic and therapeutic use. Key animal studies (especially in Syrian hamsters, and ideally with hamster-derived CP for matched antibody Fc regions) and human clinical safety and efficacy results for CP are now emerging contemporaneously. These preclinical and clinical data will be helpful to deconvolute the risk profiles for ADE versus other known severe adverse events that can occur with human CP, including transfusion-related acute lung injury96,100.

Conclusion

ADE has been observed in SARS, MERS and other human respiratory virus infections including RSV and measles, which suggests a real risk of ADE for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and antibody-based interventions. However, clinical data has not yet fully established a role for ADE in human COVID-19 pathology. Steps to reduce the risks of ADE from immunotherapies include the induction or delivery of high doses of potent neutralizing antibodies, rather than lower concentrations of non-neutralizing antibodies that would be more likely to cause ADE.

Going forwards, it will be crucial to evaluate animal and clinical datasets for signs of ADE, and to balance ADE-related safety risks against intervention efficacy if clinical ADE is observed. Ongoing animal and human clinical studies will provide important insights into the mechanisms of ADE in COVID-19. Such evidence is sorely needed to ensure product safety in the large-scale medical interventions that are likely required to reduce the global burden of COVID-19.

References

- 1.

Zhou, Y. et al. Network-based drug repurposing for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV/SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 6, 14 (2020).

- 2.

Lu, R. et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet 395, 565–574 (2020).

- 3.

Lam, T. T. et al. Identifying SARS-CoV-2 related coronaviruses in Malayan pangolins. Nature 583, 282–285 (2020).

- 4.

Hoffmann, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 181, 271–280 (2020).

- 5.

Yan, R. et al. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science 367, 1444–1448 (2020).

- 6.

Daly, J. L. et al. Neuropilin-1 is a host factor for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.05.134114v1 (2020).

- 7.

Cantuti-Castelvetri, L. et al. Neuropilin-1 facilitates SARS-CoV-2 cell entry and provides a possible pathway into the central nervous system. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.06.07.137802v1 (2020).

- 8.

Wrapp, D. et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 367, 1260–1263 (2020).

- 9.

Kim, H. W. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am. J. Epidemiol. 89, 422–434 (1969).

- 10.

Graham, B. S. Vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus: the time has finally come. Vaccine 34, 3535–3541 (2016).

- 11.

Nader, P. R., Horwitz, M. S. & Rousseau, J. Atypical exanthem following exposure to natural measles: eleven cases in children previously inoculated with killed vaccine. J. Pediatr. 72, 22–28 (1968).

- 12.

Polack, F. P. Atypical measles and enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease (ERD) made simple. Pediatr. Res. 62, 111–115 (2007).

- 13.

Dejnirattisai, W. et al. Cross-reacting antibodies enhance dengue virus infection in humans. Science 328, 745–748 (2010).

- 14.

Sridhar, S. et al. Effect of dengue serostatus on dengue vaccine safety and efficacy. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 327–340 (2018).

- 15.

Hohdatsu, T. et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection in feline alveolar macrophages and human monocyte cell line U937 by serum of cats experimentally or naturally infected with feline coronavirus. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 60, 49–55 (1998).

- 16.

Halstead, S. B. & O’Rourke, E. J. Dengue viruses and mononuclear phagocytes. I. Infection enhancement by non-neutralizing antibody. J. Exp. Med. 146, 201–217 (1977).

- 17.

Vennema, H. et al. Early death after feline infectious peritonitis virus challenge due to recombinant vaccinia virus immunization. J. Virol. 64, 1407–1409 (1990).

- 18.

Hohdatsu, T., Nakamura, M., Ishizuka, Y., Yamada, H. & Koyama, H. A study on the mechanism of antibody-dependent enhancement of feline infectious peritonitis virus infection in feline macrophages by monoclonal antibodies. Arch. Virol. 120, 207–217 (1991).

- 19.

Weiss, R. C. & Scott, F. W. Antibody-mediated enhancement of disease in feline infectious peritonitis: comparisons with dengue hemorrhagic fever. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 4, 175–189 (1981).

- 20.

Ye, Z. W. et al. Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity epitopes on the hemagglutinin head region of pandemic H1N1 influenza virus play detrimental roles in H1N1-infected mice. Front. Immunol. 8, 317 (2017).

- 21.

Winarski, K. L. et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of influenza disease promoted by increase in hemagglutinin stem flexibility and virus fusion kinetics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 15194–15199 (2019).

- 22.

Polack, F. P. et al. A role for immune complexes in enhanced respiratory syncytial virus disease. J. Exp. Med. 196, 859–865 (2002).

- 23.

Polack, F. P., Hoffman, S. J., Crujeiras, G. & Griffin, D. E. A role for nonprotective complement-fixing antibodies with low avidity for measles virus in atypical measles. Nat. Med. 9, 1209–1213 (2003).

- 24.

Gao, T. et al. Highly pathogenic coronavirus N protein aggravates lung injury by MASP-2-mediated complement over-activation. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.29.20041962v3 (2020).

- 25.

Gralinski, L. E. et al. Complement activation contributes to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus pathogenesis. mBio 9, e01753-18 (2018).

- 26.

Larsen, M. D. et al. Afucosylated immunoglobulin G responses are a hallmark of enveloped virus infections and show an exacerbated phenotype in COVID-19. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.18.099507v1 (2020).

- 27.

Chakraborty, S. et al. Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections display specific IgG Fc structures. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.05.15.20103341v1 (2020).

- 28.

Hiatt, A. et al. Glycan variants of a respiratory syncytial virus antibody with enhanced effector function and in vivo efficacy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5992–5997 (2014).

- 29.

Zeitlin, L. et al. Enhanced potency of a fucose-free monoclonal antibody being developed as an Ebola virus immunoprotectant. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 20690–20694 (2011).

- 30.

Wang, T. T. et al. IgG antibodies to dengue enhanced for FcγRIIIA binding determine disease severity. Science 355, 395–398 (2017).

- 31.

Hui, K. P. Y. et al. Tropism, replication competence, and innate immune responses of the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 in human respiratory tract and conjunctiva: an analysis in ex-vivo and in-vitro cultures. Lancet Respir. Med. 8, 687–695 (2020).

- 32.

Yip, M. S. et al. Antibody-dependent infection of human macrophages by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Virol. J. 11, 82 (2014).

- 33.

Robinson, W. E. Jr, Montefiori, D. C. & Mitchell, W. M. Antibody-dependent enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Lancet 1, 790–794 (1988).

- 34.

Robinson, W. E. Jr et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in vitro by serum from HIV-1-infected and passively immunized chimpanzees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 4710–4714 (1989).

- 35.

Takada, A., Watanabe, S., Okazaki, K., Kida, H. & Kawaoka, Y. Infectivity-enhancing antibodies to Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 75, 2324–2330 (2001).

- 36.

Takada, A., Feldmann, H., Ksiazek, T. G. & Kawaoka, Y. Antibody-dependent enhancement of Ebola virus infection. J. Virol. 77, 7539–7544 (2003).

- 37.

Ochiai, H. et al. Infection enhancement of influenza A NWS virus in primary murine macrophages by anti-hemagglutinin monoclonal antibody. J. Med. Virol. 36, 217–221 (1992).

- 38.

Sariol, C. A., Nogueira, M. L. & Vasilakis, N. A tale of two viruses: does heterologous flavivirus immunity enhance Zika disease? Trends Microbiol. 26, 186–190 (2018).

- 39.

Wan, Y. et al. Molecular mechanism for antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus entry. J. Virol. 94, e02015-19 (2020).

- 40.

Jaume, M. et al. Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike antibodies trigger infection of human immune cells via a pH- and cysteine protease-independent FcγR pathway. J. Virol. 85, 10582–10597 (2011).

- 41.

Cheung, C. Y. et al. Cytokine responses in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-infected macrophages in vitro: possible relevance to pathogenesis. J. Virol. 79, 7819–7826 (2005).

- 42.

Yip, M. S. et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS coronavirus infection and its role in the pathogenesis of SARS. Hong Kong Med. J. 22, 25–31 (2016).

- 43.

Ana-Sosa-Batiz, F. et al. Influenza-specific antibody-dependent phagocytosis. PLoS ONE 11, e0154461 (2016).

- 44.

Yasui, F. et al. Phagocytic cells contribute to the antibody-mediated elimination of pulmonary-infected SARS coronavirus. Virology 454–455, 157–168 (2014).

- 45.

Zhou, J. et al. Active replication of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and aberrant induction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in human macrophages: implications for pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 209, 1331–1342 (2014).

- 46.

Ho, M. S. et al. Neutralizing antibody response and SARS severity. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11, 1730–1737 (2005).

- 47.

Zhao, J. et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients of novel coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa344 (2020).

- 48.

Liu, Y. et al. Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20, 656–657 (2020).

- 49.

Zheng, S. et al. Viral load dynamics and disease severity in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Zhejiang province, China, January–March 2020: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 369, m1443 (2020).

- 50.

Long, Q. X. et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat. Med. 26, 1200–1204 (2020).

- 51.

Sekine, T. et al. Robust T cell immunity in convalescent individuals with asymptomatic or mild COVID-19. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.017 (2020).

- 52.

Mathew, D., Giles, J. R., Baxter, A. E., Oldridge, D. A. & Greenplate, A. R. Deep immune profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals distinct immunotypes with therapeutic implications. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc8511 (2020).

- 53.

Tetro, J. A. Is COVID-19 receiving ADE from other coronaviruses? Microbes Infect. 22, 72–73 (2020).

- 54.

Khan, S. et al. Analysis of serologic cross-reactivity between common human coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2 using coronavirus antigen microarray. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.24.006544v1 (2020).

- 55.

Tseng, C. T. et al. Immunization with SARS coronavirus vaccines leads to pulmonary immunopathology on challenge with the SARS virus. PLoS ONE 7, e35421 (2012).

- 56.

Deming, D. et al. Vaccine efficacy in senescent mice challenged with recombinant SARS-CoV bearing epidemic and zoonotic spike variants. PLoS Med. 3, e525 (2006).

- 57.

Bolles, M. et al. A double-inactivated severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine provides incomplete protection in mice and induces increased eosinophilic proinflammatory pulmonary response upon challenge. J. Virol. 85, 12201–12215 (2011).

- 58.

Yasui, F. et al. Prior immunization with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS)-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) nucleocapsid protein causes severe pneumonia in mice infected with SARS-CoV. J. Immunol. 181, 6337–6348 (2008).

- 59.

Agrawal, A. S. et al. Immunization with inactivated Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus vaccine leads to lung immunopathology on challenge with live virus. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 12, 2351–2356 (2016).

- 60.

Weingartl, H. et al. Immunization with modified vaccinia virus Ankara-based recombinant vaccine against severe acute respiratory syndrome is associated with enhanced hepatitis in ferrets. J. Virol. 78, 12672–12676 (2004).

- 61.

Czub, M., Weingartl, H., Czub, S., He, R. & Cao, J. Evaluation of modified vaccinia virus Ankara based recombinant SARS vaccine in ferrets. Vaccine 23, 2273–2279 (2005).

- 62.

Honda-Okubo, Y. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus vaccines formulated with delta inulin adjuvants provide enhanced protection while ameliorating lung eosinophilic immunopathology. J. Virol. 89, 2995–3007 (2015).

- 63.

Hashem, A. M. et al. A highly immunogenic, protective, and safe adenovirus-based vaccine expressing Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus S1-CD40L fusion protein in a transgenic human dipeptidyl peptidase 4 mouse model. J. Infect. Dis. 220, 1558–1567 (2019).

- 64.

London, A. J. & Kimmelman, J. Against pandemic research exceptionalism. Science 368, 476–477 (2020).

- 65.

Lurie, N., Saville, M., Hatchett, R. & Halton, J. Developing Covid-19 vaccines at pandemic speed. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1969–1973 (2020).

- 66.

Liu, L. et al. Anti-spike IgG causes severe acute lung injury by skewing macrophage responses during acute SARS-CoV infection. JCI Insight 4, e123158 (2019).

- 67.

Wang, Q. et al. Immunodominant SARS coronavirus epitopes in humans elicited both enhancing and neutralizing effects on infection in non-human primates. ACS Infect. Dis. 2, 361–376 (2016).

- 68.

Luo, F. et al. Evaluation of antibody-dependent enhancement of SARS-CoV infection in rhesus macaques immunized with an inactivated SARS-CoV vaccine. Virol. Sin. 33, 201–204 (2018).

- 69.

Qin, E. et al. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy in monkeys of purified inactivated Vero-cell SARS vaccine. Vaccine 24, 1028–1034 (2006).

- 70.

Kam, Y. W. et al. Antibodies against trimeric S glycoprotein protect hamsters against SARS-CoV challenge despite their capacity to mediate FcγRII-dependent entry into B cells in vitro. Vaccine 25, 729–740 (2007).

- 71.

Yang, Z. Y. et al. A DNA vaccine induces SARS coronavirus neutralization and protective immunity in mice. Nature 428, 561–564 (2004).

- 72.

Bukreyev, A. et al. Mucosal immunisation of African green monkeys (Cercopithecus aethiops) with an attenuated parainfluenza virus expressing the SARS coronavirus spike protein for the prevention of SARS. Lancet 363, 2122–2127 (2004).

- 73.

Bisht, H. et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein expressed by attenuated vaccinia virus protectively immunizes mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 6641–6646 (2004).

- 74.

Gao, Q. et al. Rapid development of an inactivated vaccine candidate for SARS-CoV-2. Science 369, 77–81 (2020).

- 75.

Chan, J. F. et al. Simulation of the clinical and pathological manifestations of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in golden Syrian hamster model: implications for disease pathogenesis and transmissibility. Clin. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa325 (2020).

- 76.

Ju, B. et al. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature 584, 115–119 (2020).

- 77.

Brouwer, P. J. M. et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies from COVID-19 patients define multiple targets of vulnerability. Science 369, 643–650 (2020).

- 78.

Hansen, J. et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science 369, 1010–1014 (2020).

- 79.

Yuan, M. et al. A highly conserved cryptic epitope in the receptor binding domains of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV. Science 368, 630–633 (2020).

- 80.

Shi, R. et al. A human neutralizing antibody targets the receptor-binding site of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 584, 120–124 (2020).

- 81.

Cao, Y. et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent patients’ B cells. Cell 182, 73–84 (2020).

- 82.

Rogers, T. F. et al. Isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science 369, 956–963 (2020).

- 83.

Halstead, S. B. Neutralization and antibody-dependent enhancement of dengue viruses. Adv. Virus. Res. 60, 421–467 (2003).

- 84.

DiLillo, D. J., Palese, P., Wilson, P. C. & Ravetch, J. V. Broadly neutralizing anti-influenza antibodies require Fc receptor engagement for in vivo protection. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 605–610 (2016).

- 85.

Liu, Y. et al. Cross-lineage protection by human antibodies binding the influenza B hemagglutinin. Nat. Commun. 10, 324 (2019).

- 86.

Hessell, A. J. et al. Fc receptor but not complement binding is important in antibody protection against HIV. Nature 449, 101–104 (2007).

- 87.

Parsons, M. S. et al. Fc-dependent functions are redundant to efficacy of anti-HIV antibody PGT121 in macaques. J. Clin. Invest. 129, 182–191 (2019).

- 88.

Crowley, A. R. & Ackerman, M. E. Mind the gap: how interspecies variability in IgG and its receptors may complicate comparisons of human and non-human primate effector function. Front. Immunol. 10, 69 (2019).

- 89.

Mair-Jenkins, J. et al. The effectiveness of convalescent plasma and hyperimmune immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe acute respiratory infections of viral etiology: a systematic review and exploratory meta-analysis. J. Infect. Dis. 211, 80–90 (2015).

- 90.

Ko, J. H. et al. Challenges of convalescent plasma infusion therapy in Middle East respiratory coronavirus infection: a single centre experience. Antivir. Ther. 23, 617–622 (2018).

- 91.

Cheng, Y. et al. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in SARS patients in Hong Kong. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 24, 44–46 (2005).

- 92.

Shen, C. et al. Treatment of 5 critically ill patients with COVID-19 with convalescent plasma. JAMA 323, 1582–1589 (2020).

- 93.

Duan, K. et al. Effectiveness of convalescent plasma therapy in severe COVID-19 patients. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 9490–9496 (2020).

- 94.

Ahn, J. Y. et al. Use of convalescent plasma therapy in two COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome in Korea. J. Korean Med. Sci. 35, e149 (2020).

- 95.

Zhang, B. et al. Treatment with convalescent plasma for critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Chest 158, e9–e13 (2020).

- 96.

Joyner, M. J. et al. Early safety indicators of COVID-19 convalescent plasma in 5,000 patients. J. Clin. Invest. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI140200 (2020).

- 97.

Li, L. et al. Effect of convalescent plasma therapy on time to clinical improvement in patients with severe and life-threatening COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 324, 460–470 (2020).

- 98.

Gharbharan, A. et al. Convalescent plasma for COVID-19. A randomized clinical trial. Preprint at https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.07.01.20139857v1 (2020).

- 99.

Casadevall, A. & Pirofski, L. A. The convalescent sera option for containing COVID-19. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 1545–1548 (2020).

- 100.

Pandey, S. & Vyas, G. N. Adverse effects of plasma transfusion. Transfusion 52 (Suppl. 1), 65S–79S (2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Victorian government, Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence in Convergent Bio-Nano Science and Technology (S.J.K.), an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) programme grant no. 1149990 (S.J.K.), NHMRC project grant no. 1162760 (A.K.W.), NHMRC fellowships to S.J.K. and A.K.W., the United States National Institutes of Health grant nos. 1DP5OD023118 and R21AI143407 (B.J.D.), the COVID-19 Fast Grants programme (B.J.D.) and the Jack Ma Foundation (B.J.D.).

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, W.S., Wheatley, A.K., Kent, S.J. et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement and SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and therapies. Nat Microbiol 5, 1185–1191 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-00789-5

- Received

- Accepted

- Published

- Issue Date

- DOIhttps://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-020-00789-5