The study from Great Britain discovered microplastic particles in the lung tissue of 11 out of 13 patients undergoing surgery.

Published on By Amanda Brown

Microplastic fibres were found deep in the lower lungs of living human beings in almost every person sampled in a recent UK study.

The study from Great Britain discovered microplastic particles — present in many COVID-19 masks — in the lung tissue of 11 out of 13 patients undergoing surgery.

Polypropylene (PP) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) were the most prevalent substances present in the lungs.

The microscopic plastic fragments and fibres were discovered by scientists at Hull York Medical School in the UK. Some of the filaments were two millimetres long in patients undergoing surgery whose lung tissue they sampled.

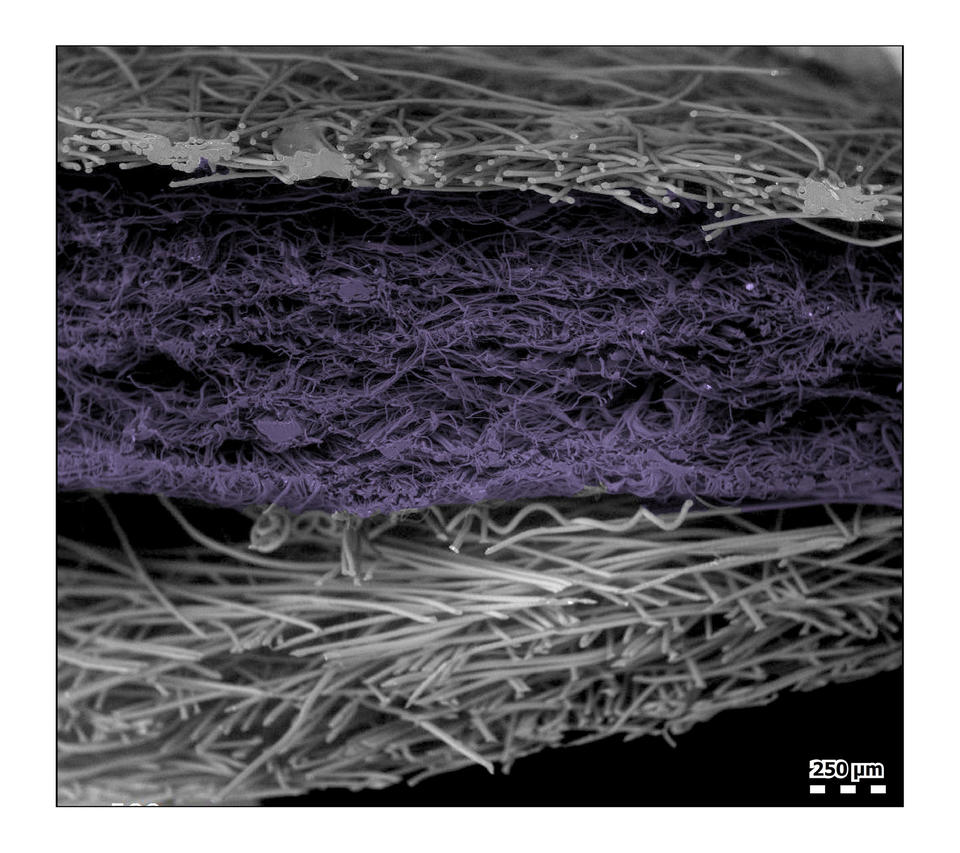

The plastic dust and microscopic debris comprises the same plastics used to manufacture the ubiquitous surgical masks worn by hundreds of millions of people around the world as mandated by governments in an attempt to halt the spread of COVID-19.

The material most commonly used to make these masks is PP — PP fabric is made from a “thermoplastic” polymer, meaning that it’s easy to work with and shape at high temperatures.

Blue surgical masks can also be made of polystyrene, polycarbonate, polyethylene, or polyester, all of which are types of fabrics derived from thermoplastic polymers.

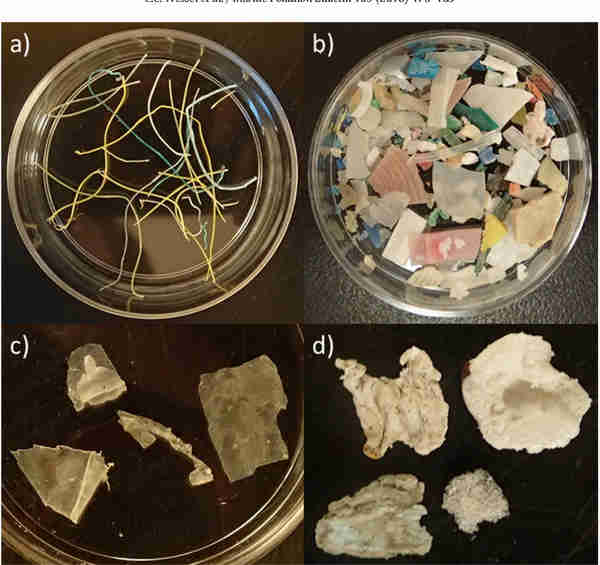

Disposable blue masks are to be found littering almost every city street in the developed world after two years of COVID-19 mandates ruled that masks should be worn in most indoor environments much of the time. Healthy adults, children, the immunocompromised, and the elderly have all been subject to mask mandates.

Microplastics were detected in human blood for the first time in March, showing the particles can travel around the human body and may become embedded in organs. The impact on health is still to be determined.

Researchers are concerned because microplastics cause damage to human cells in the laboratory and air pollution particles are already known to enter the body and cause millions of premature deaths each year.

“Airborne microplastics (MPs) have been sampled globally, and their concentration is known to increase in areas of high human population and activity, especially indoors. Respiratory symptoms and disease following exposure to occupational levels of MPs within industry settings have also been reported,” the UK study said. “In total, 39 MPs were identified within 11 of the 13 lung tissue samples… These results support inhalation as a route of exposure for environmental MPs, and this characterization of types and levels can now inform realistic conditions for laboratory exposure experiments, with the aim of determining health impacts.”

“We did not expect to find the highest number of particles in the lower regions of the lungs, or particles of the sizes we found,” said Laura Sadofsky, at Hull York Medical School in the UK, a senior author of the study. “It is surprising as the airways are smaller in the lower parts of the lungs and we would have expected particles of these sizes to be filtered out or trapped before getting this deep.”

“This data provides an important advance in the field of air pollution, microplastics, and human health,” she said.

The research used samples of healthy lung tissue from next to the lung region targeted for surgery. It analyzed particles as small as .003mm in size and used spectroscopy to identify plastic types.

It also used control samples to account for the level of background contamination. The study has been accepted for publication by the journal Science of the Total Environment.

An older study published in 2020 looked into the risks associated with mask-wearing and the inhalation of microplastics. The study concluded:

main (smaller)• Wearing masks poses microplastic inhalation risk, reusing masks increases the risk

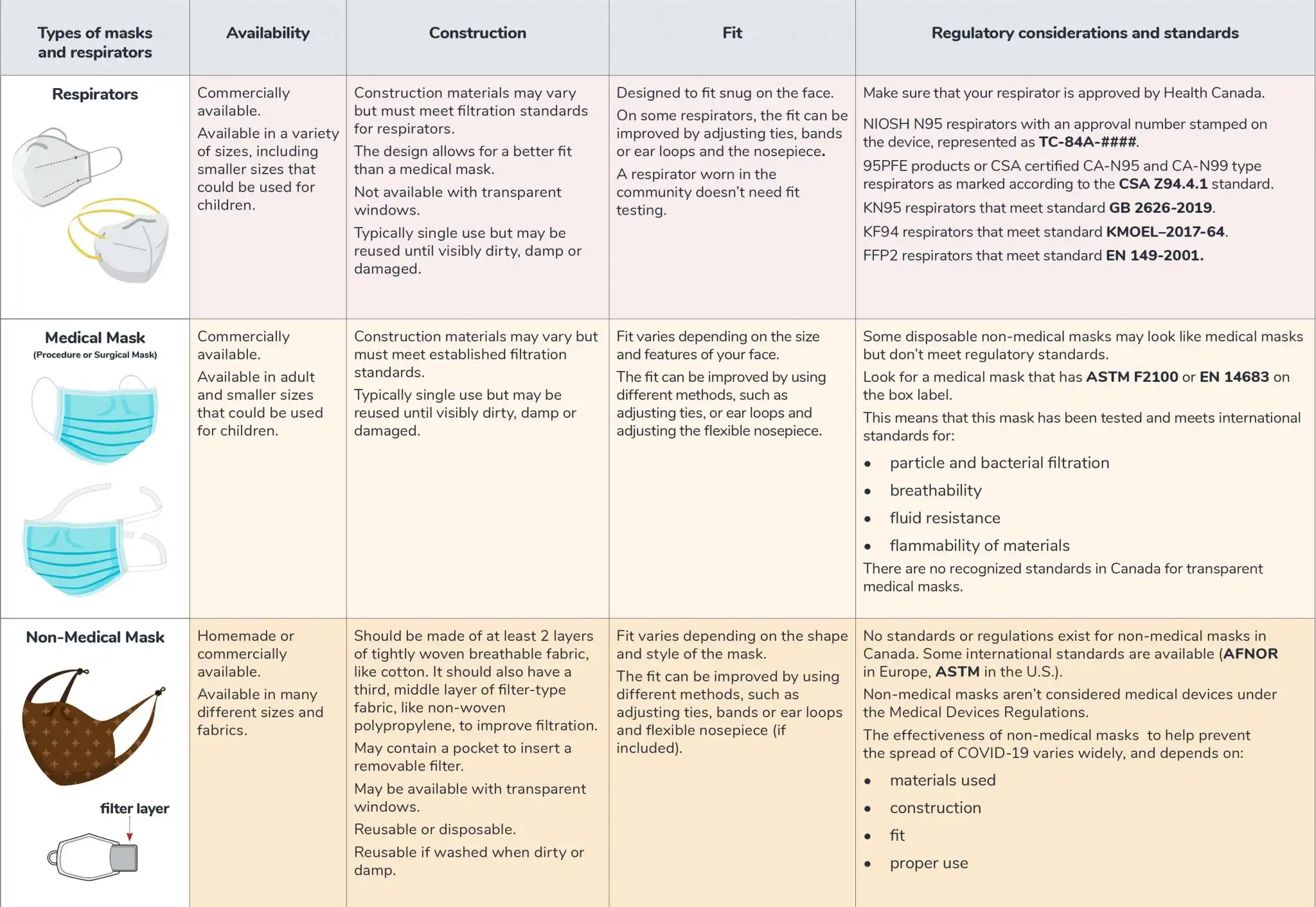

• Wearing N95 masks poses lowest microplastic inhalation risks in the long term

• Wearing masks, except for N95, poses higher stripe type microplastic inhalation risk

• Wearing masks poses considerably lower spherical-type microplastic inhalation risk

• Wearing masks leads to lower gross microplastic inhalation risk in the long term

“Surgical, cotton, fashion, and activated carbon masks wearing pose higher fibre-like microplastic inhalation risk, while all masks generally reduced exposure when used under their supposed time (<4 h),” the study said.

Chris Schaefer is a respirator specialist and onsite training expert based in Edmonton, Alta. He has been teaching and conducting respirator fit testing for more than 20 years with his company, SafeCom Training Services Inc. His clients include government departments, Canada’s military, Alberta Health Services, educational institutions, and private industry. Schaefer is a published author and a recognized authority on the subject of respirators and masks.

The Western Standard asked Schaefer if he believed surgical masks of the type used by millions of Canadians, and people throughout the world, presented a significant risk of microplastic inhalation from the masks themselves. He began by clarifying that the face covering generally referred to as a ‘mask’ is not, in fact, a mask, at all.

Schaefer refers to COVID-19 face coverings as “breathing barriers.”

“What has been mandated in hospitals and through the general public through this whole COVID-19 agenda, are not masks. They don’t meet the legal definition [of a mask,] “Shaefer said. “A [proper] mask has engineered breathing openings in front of mouth and nose to ensure easy and effortless breathing. A breathing barrier is closed both over mouth and nose. And by doing that, it captures carbon dioxide that you exhale, forces you to re-inhale it, causing a reduction in your inhaled oxygen levels and causes excessive carbon dioxide. So they’re not safe to wear.”

Schaefer was emphatic when asked if he believed the surgical masks in general use were shedding inhaled microplastics.

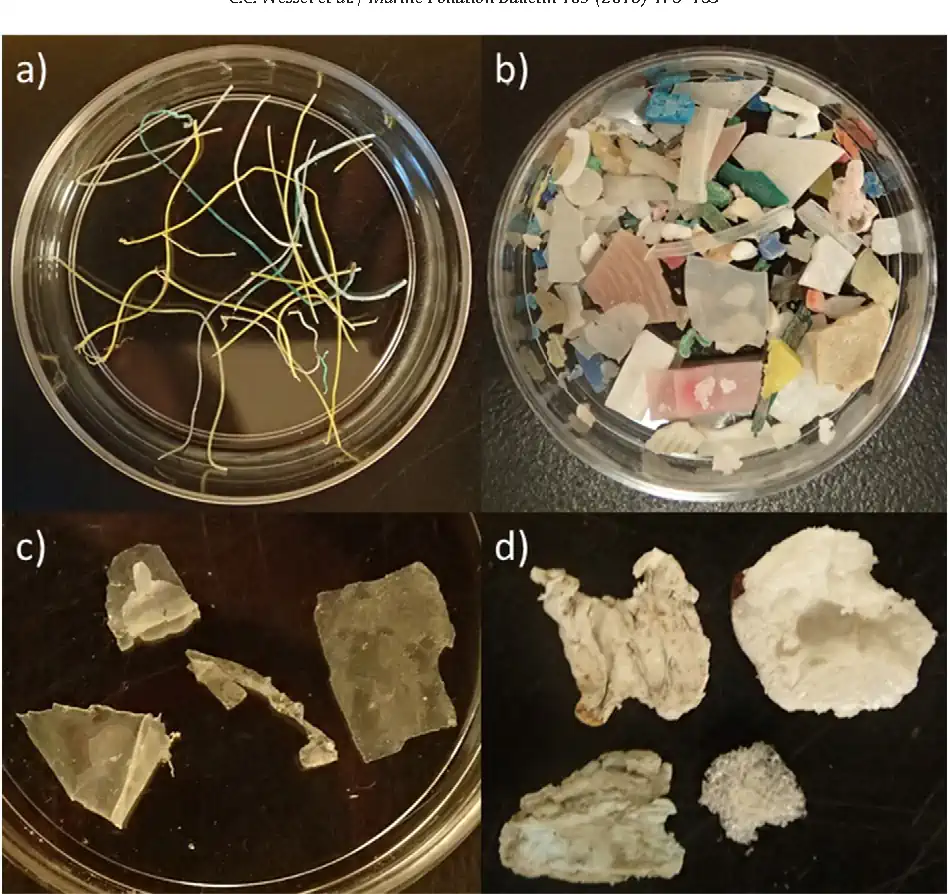

“As far as whether it could cause somebody to inhale the polypropylene fibres that are used to make this and synthetic polymers that are used to make the filtration of these devices — absolutely. Take a pair of scissors and cut one open. You can see that in between the two main covers that are encapsulating, these loose fibres are breaking away. They’re becoming dislodged from the cover itself, just through normal wear and tear and the agitation of putting it on and taking it off,” Schaefer said.

“The heat and moisture that it captures will cause the degradation of those fibres to break down smaller. Absolutely, people are inhaling [microplastic particles]. I’ve written very extensively on the hazards of these breathing barriers the last two years, I’ve spoken to scientists [and other] people for the last two years about people inhaling the fibres. If you get the sensation that you’ve gotten a little bit of cat hair, or any type of irritation in the back of your throat after wearing them,” said Schrieffer. “That means you’re inhaling the fibres.”

Schaefer said we will have to wait to see the the long-term effects of the inhalation of microplastics from masks.

“So we know that people are inhaling the fibres. What the risks are going to be, what the effects are going to be — it could be anything — but it could definitely cause lung inflammation and could cause full-body inflammation. Absolutely,” Schaefer said.

“This is not normal. Anybody who would normally be exposed to any type of synthetic polymers or polypropylene fibres [in an occupational environment] would have to wear approved respiratory protection. These breathing barriers are not respirators. These fibres break down to between .2 mm, and the large ones are five mm. So they’re totally inhalable, they break down very small and and, well, what that’s going to do to people in the in the form of lung function — as well as toxicity overload in their body — I guess we’ll know in a few years.

Although the latter study assessed the masks’ abilities to filter incoming environmental microplastics, the study did not assess whether particles were shed from the construction of the mask fabric itself on its alternate side — particles that would enter the lungs of a wearer.

Amanda Brown is a reporter with the Western Standard

abrown@westernstandardonline.com

Twitter: @WS_JournoAmanda